Waldo Tobler is a geographer at my alma mater, UC Santa Barbara. He is known for Tobler’s Law or the “first law of geography” which states “Everything is related to everything else, but near things are more related to each other than distant things.”

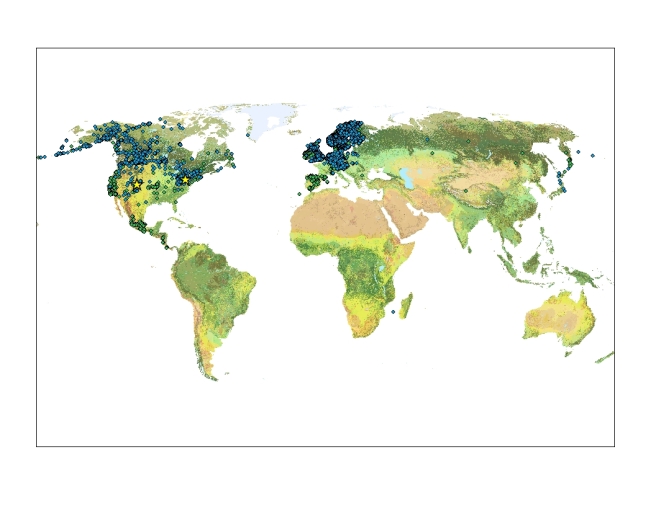

My classmate Sunil Bharuchi recently published a discussion of Tobler’s Law on his blog, GIS 295 Web GIS. He included this image, which explains spatial auto correlation.

Spatial autocorrelation measures how well a set of spatial features and their values are clustered together in space. A spatial feature is a point, line or polygon that identifies the geographic location of a real world object; this object could be a building, a forest, a rock unit or a lake.

According to Tobler’s law, spatial features will be clustered next to more similar spatial features – this is illustrated in the first image above. But, is this always true? Sunil’s post got me thinking.

Here is a geologic map of Yosemite National Park. Which of the images above does it look like?

“Map of Yosemite National Park” by General_geologic_map_of_Yosemite_area.png: en:United States Geological Survey derivative work: Grandiose – This file was derived from General geologic map of Yosemite area.png: . Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Commons.

I’ve spent years looking at geologic maps, so I told Sunil “image three looks more like geology.” But, does that mean Tobler is wrong?

Not at all.

Nicolas Steno (Niels Stensen, 1638-1686) was a Danish scientist and bishop who made important contributions to the fields of anatomy, paleontology, crystallography and geology. Steno’s principles of statigraphy explain the formation of sedimentary rock and are still used by geologists to determine the history of a rock unit. There are three principles:

- The Principle of Superposition: When sediments are deposited, the sediment that is deposited first is at the bottom while sediment that is deposited later is at the top. Therefore, the lower sediments are older.

- The Principle of Original Horizontality: Sediment is originally deposited in horizontal layers.

- The Principle of Original Continuity: Sediment is deposited in continuous sheets that only stop when they meet an obstacle or taper off because of distance from the source.

Doesn’t the Principle of Original Horizontality sound a lot like Tobler’s Law? Then why don’t geological maps look like the first picture on Sunil’s image?

First of all, sedimentary rock isn’t the only type of rock on Earth.Steno’s principles do not apply to igneous and metamorphic rock.

Second, the Earth is an active planet. Plate tectonics causes sedimentary layers to bend, break and even overturn. Igneous rocks intrude into existing rock from below the Earth’s surface or erupt from above. These processes mean that geologic units are often very complex and the resulting spatial patterns reflect that complexity.

“Yosemite USA” by GuyFrancis – Own work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Commons.

James Hutton (1726-1997) was a Scottish physician and geologist who is known as the founder of modern geology. He was the first to suggest that the Earth is continually being formed and that based on the rates of geologic processes, the Earth must be much,much older than the accepted estimate of a few thousand years. He is also known for the Law of Cross-cutting Relationships.

Law of Cross-cutting Relationships: If a fault or other body of rock cuts through another body of rock, then that intrusion must be younger in age than the rock that it cuts or displaces.

It is this Law of Cross-cutting Relationships that helps us interpret geological units and create geological maps.

Can you figure out the temporal relationships in this cross section?

-

From Earth: Portrait of a Planet, 4th Edition (2011) by Stephen Marshak.

So, how does Tobler’s Law fit in? It depends on scale. If you are standing on an outcrop of sandstone, chances are good that the rock surrounding you will also be sandstone – especially if you are in the tectonically quieter center of a continent. But, If you are mapping Yosemite park using one kilometer pixels, you will find a lot more variation in neighboring areas.

What is going on? Did New York City specifically zone these locations to have tall buildings? Is this meant to preserve the skyline? Or, is it intended to show the importance of the Financial District?

What is going on? Did New York City specifically zone these locations to have tall buildings? Is this meant to preserve the skyline? Or, is it intended to show the importance of the Financial District?