The human eye is a light sensor. We can see because the objects around us emit or reflect light at wavelengths that our eyes can detect.

Remote sensing detectors work in the same way. Sunlight is reflected from Earth’s surface. Satellite sensors detect that light and create images. But, satellite and aerial sensors are a lot more sensitive than our eyes.

Our eyes can only detect light with wavelengths from about 390 nanometers to 700 nanometers. This range is called visible light and is shown as a rainbow in the NASA image below. But, satellites can detect a much wider range of wavelengths, depending on the sensor. Landsat satellites detect light from visible blue (450 nm) to the thermal infrared (1251 nm).

All objects reflect, absorb and transmit light. But, some types of materials reflect and absorb certain wavelengths of light in very characteristic ways. So, these types of materials can be distinguished from each other based on the differences in reflectance, or the differences in the pattern of wavelengths that are detected by the sensor. The pattern is called a spectral signature. The following image from NASA shows spectral signatures for some common Earth materials.

(If you click on the picture, it will take you to a NASA site that explains light and remote sensing in more detail.)

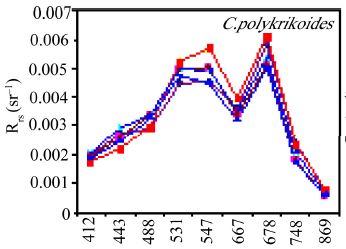

Harmful algal blooms also have spectral signatures. This is the spectral signature of Cochlodinium polykrikoides, one of the species that causes HABs in Virginia (Simon and Shanmugam, 2012).

C. polykrikoides is known to absorb light at 555 nanometers and reflect it at 678 nanometers. These wavelengths correspond to the high and low peaks in the image above.

There is a lot of research about C. polykrikoides, but very little is known about the spectral signature of Alexandrium monilatum. I decided that I would use the hyperspectral data that was collected on our Golden Day of Data Collection, August 17, 2015 to identify blooms of C. polykrikoides and I would try to decode the spectral signature of Alexandrium blooms.

I had a plan. I would map the chlorophyll measurements from the data cruises on the Landsat image to identify the areas with the most chlorophyll. I believed this would correspond to the blooms. I would join these areas to the hyperspectral images in order to obtain spectral signatures. Then, I could map the extent of each bloom.

It was a plan, but you know they say about plans….

Stay tuned for Harmful Algal Blooms Part 5: Trouble in Data Land.

2 thoughts on “Harmful Algal Blooms – Part 4: What is a Spectral Signature?”